1606

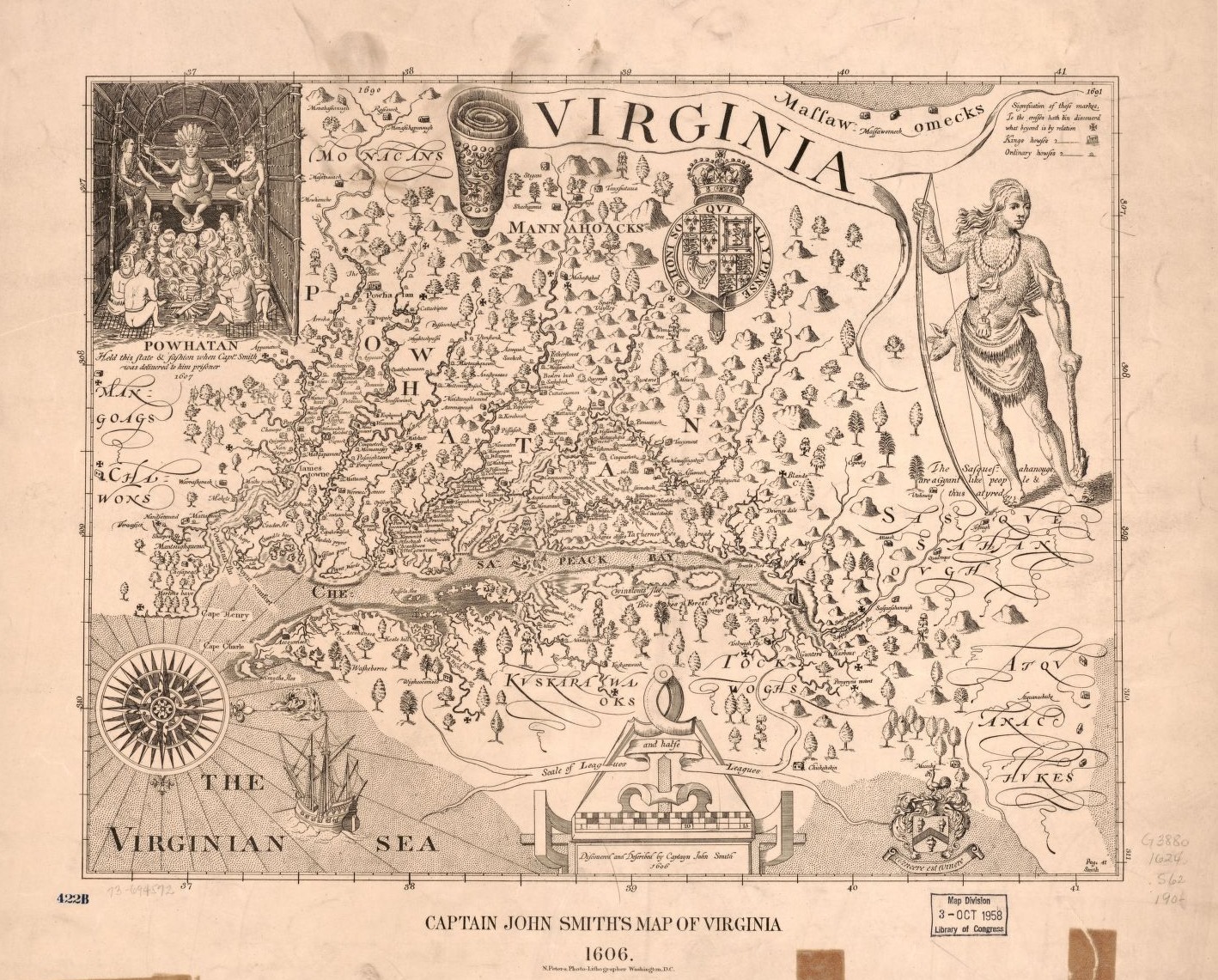

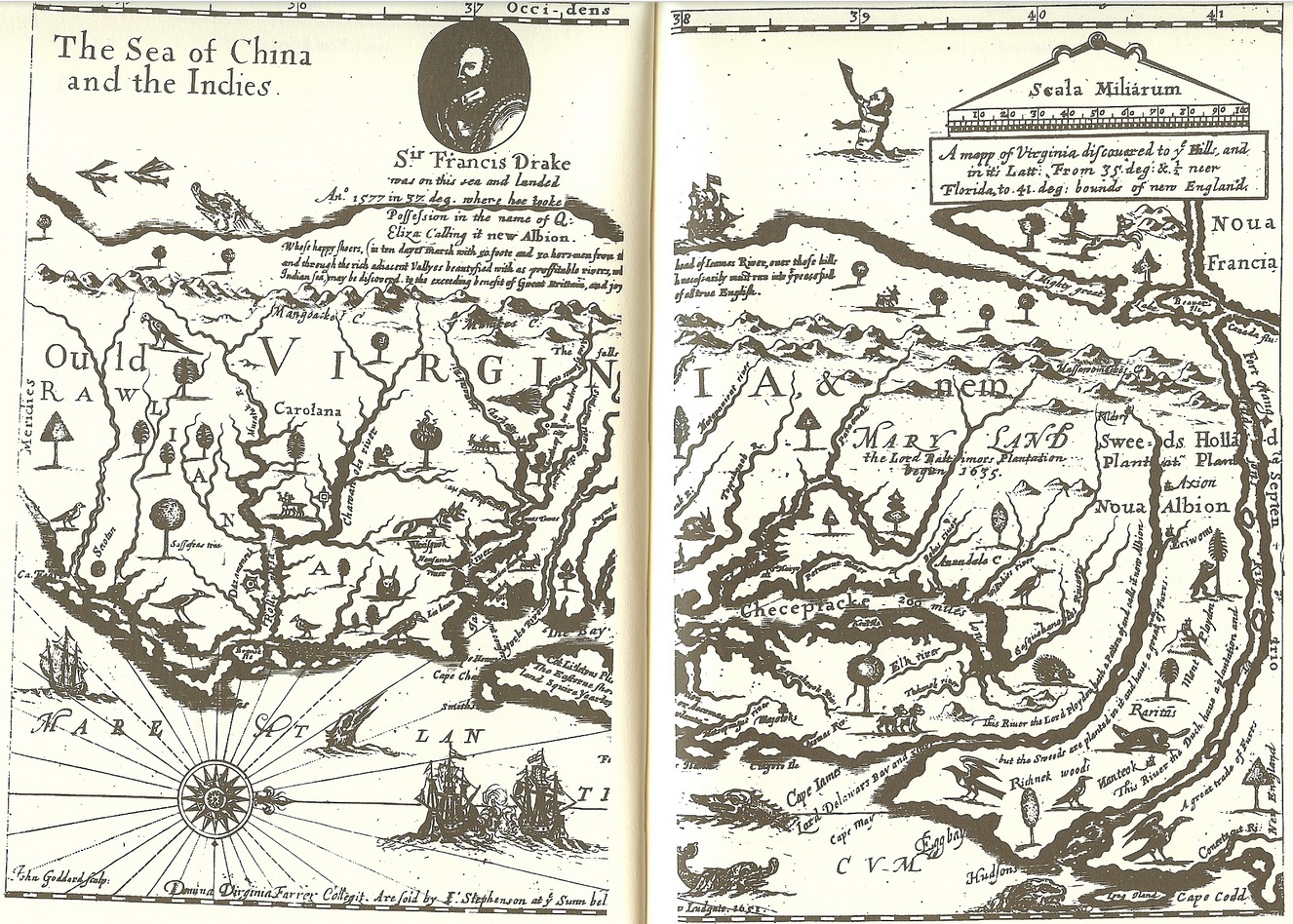

John Smith puts “Mangoags” on the southwest section of his 1612 map of Virginia, indicating Meherrin territory.

1646

The Nottoway, Iroquoian-speakers whose territory lay along the Nottoway River in the upper Chowan drainage, resided within the Virginia-North Carolina coastal plain. Like their neighbors, the Tuscarora and Meherrin, they were agriculturalists who relied heavily on hunting and gathering. The Nottoway’s remoteness from the more thickly settled part of the Virginia colony spared them from European intrusion until the mid-seventeenth century. However, they were seated only 32 miles from Fort Henry, a trading post and military garrison built at the falls of the Appomattox River in 1646.

COLONIAL (National Park Service)

A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

CHAPTER 4:

Narrative History

Martha W. McCartney

1646

Dudley Map 1646

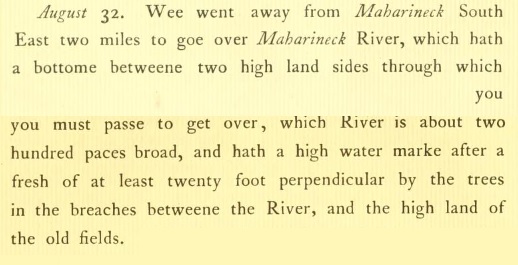

1650

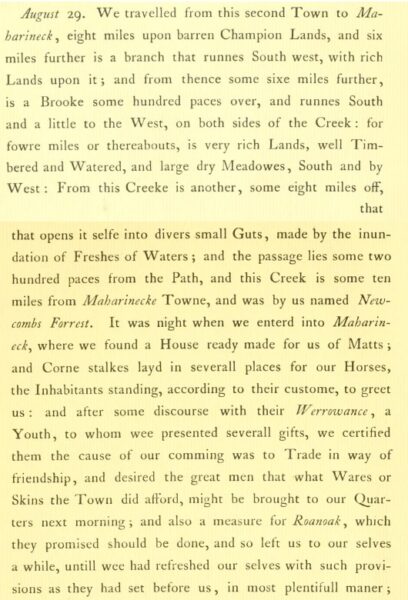

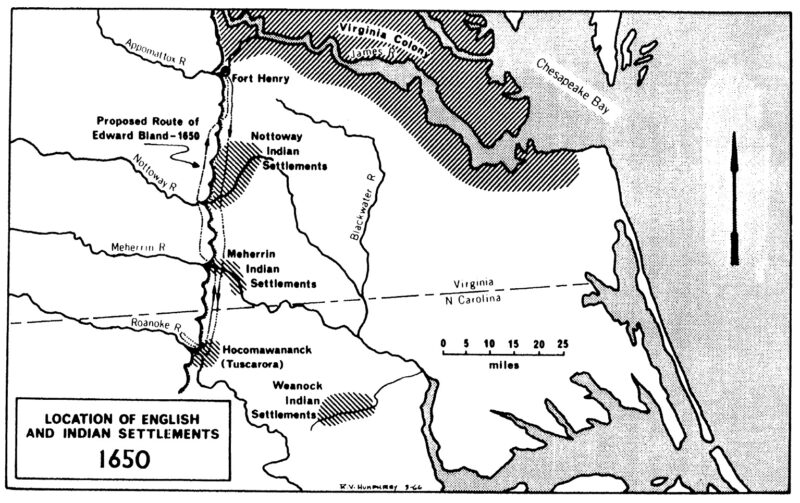

On Aug 29, 1650 Edward Bland led an expedition into a Meherrin village called Maharineck.

The Discovery of New Brittaine. By Edward Bland.

1650

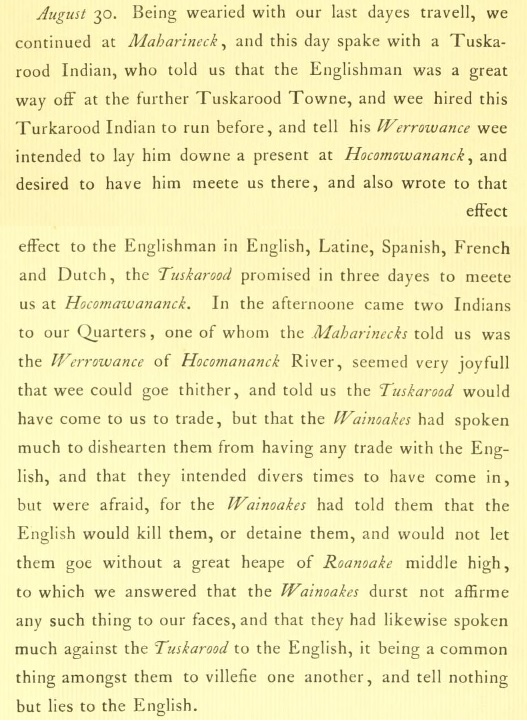

Aug 30, 1650

Edward Blands speaks with a Tuskarood Indian while visiting the Meherrin village of Maharineck.

The Discovery of New Brittaine. By Edward Bland.

1650

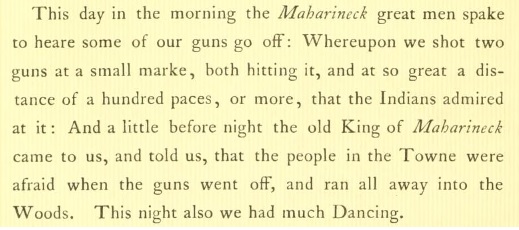

Aug 31, 1650

The Discovery of New Brittaine. By Edward Bland.

1650

Aug 32, 1650

The Discovery of New Brittaine. By Edward Bland.

1650

In 1650, Bland visited the Meherrin and provided a record of low social

stratification, a serious investment in international trade, and a separate ethnic identity. His

account also provides information on relations between the Meherrin and the Tuscarora,

Chowanoke, and Powhatan prior to 1650. We know that cross-group marriage ties, and even bride capture, were not uncommon occurrences.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 89)

1650

1650

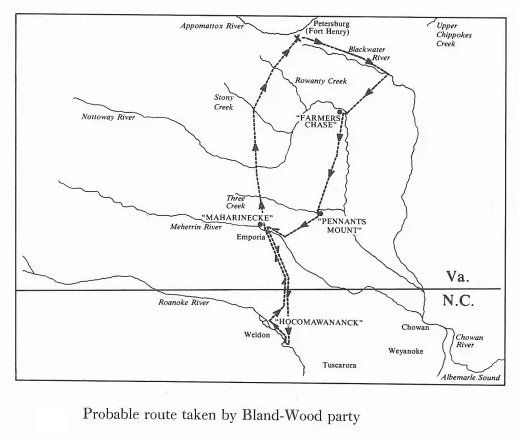

1651

Sir Edward Bland’s map included in his 1651 pamphlet published in London the following year after his exploration to the Chowan, Meherrin, and Roanoke river area were he met with the Tuscarora and Meherrin Indians.

1660

Most of the information on the Meherrin’s early movements comes from depositions

given by Englishmen between 1707 and 1711, who were queried in an investigation of the

Virginia-Carolina boundary dispute (see Documents B-21, B-22, B-27, B-28, B-29, B-39). These

men were early settlers along the Meherrin or Chowan Rivers and had personal and frequent

contacts with the Meherrin. Two of them, Thomas Wynn and Thomas Briggs, had served as the

Meherrin’s official interpreters in colonial business. Although their memory may not be perfect,

the authority of the deponents is indisputable (assuming, of course, they did not conspire to

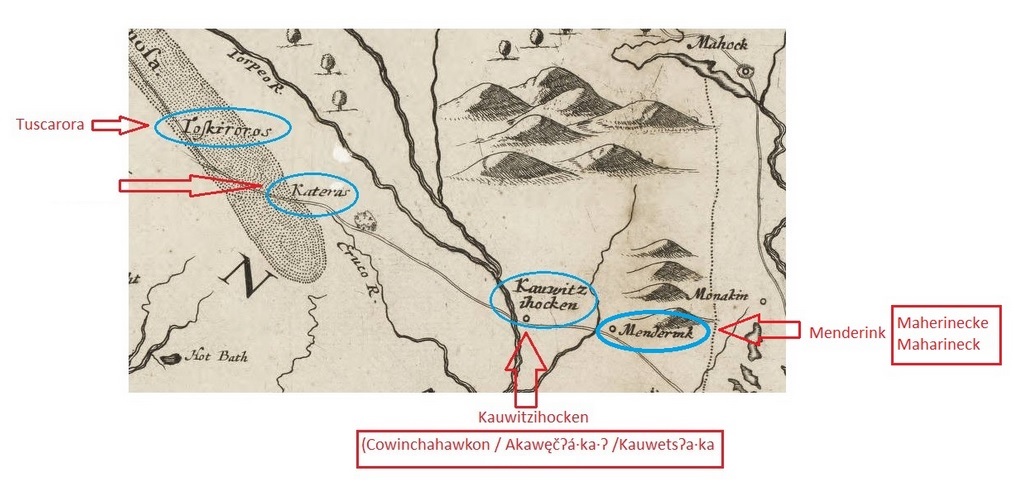

commit perjury). According to their testimony, the Meherrin lived at two villages upstream in Virginia ca. 1660: Cowinchahawkon and Unote.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 74)

1665

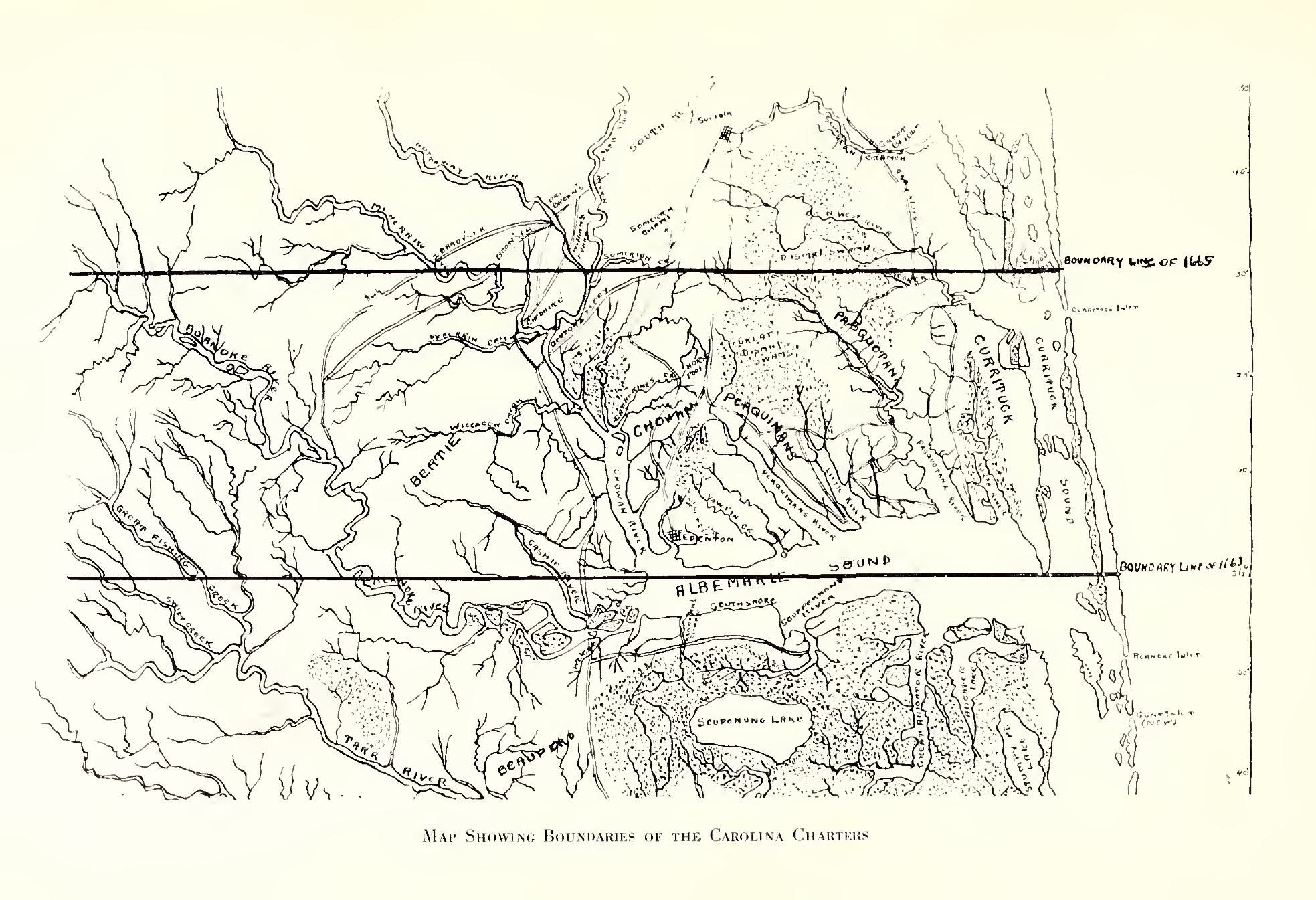

Map Showing Boundaries of the Carolina Charters. (Boundary Lines for 1665 and 1663).

1667

We know the Meherrin had vacated Unote by

the year 1667, as the Weyanokes, in their perpetual flight, had settled there for a season upon “old fields.” The Meherrin then reoccupied the Unote site at some point and remained there until the mid-1680s.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 74)

1667

In 1667, Richard Booth, with another

Englishman and a Weyanoke Indian, made a trip up the river by canoe to trade at the “Meherrin

towns” (Document B-22).

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 72)

1667

Deposition of Richard Booth “…in the year 1667 he being employed by one William West to go in a Canoe with Certain goods &c. to the Maherine Indian Towns one Jno Browne and a certain Weyanoke Indian called Tom Frusman being in the Canoe with him as they went down Blackwater River…”

North Carolina Colonial Records (Saunders) I: 661-662. January, 1707.

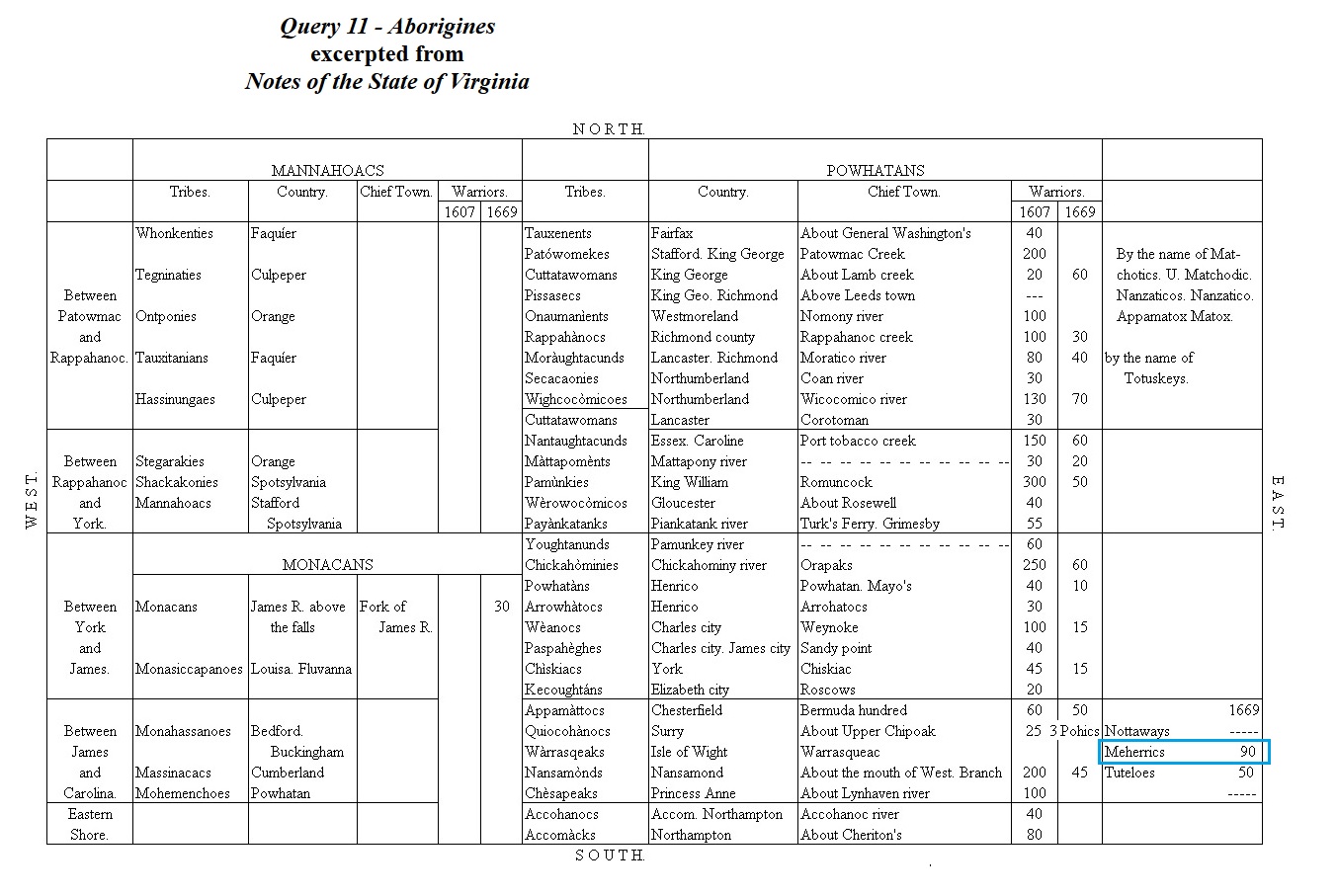

1669

The preceding table contains a state of these several tribes, according to their confederacies and geographical situation, with their numbers when we first became acquainted with them, where these numbers are known. The numbers of some of them are again stated as they were in the year 1669, when an attempt was made by the assembly to enumerate them. Probably the enumeration is imperfect, and in some measure conjectural, and that a further search into the records would furnish many more particulars. What would be the melancholy sequel of their history, may however be augured from the census of 1669

1669

Virginia census, the Meherrins are listed as the “Menheyricks.” (Hodge, Frederick Webb. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico .

University of Michigan. 1910. p 33)

1669

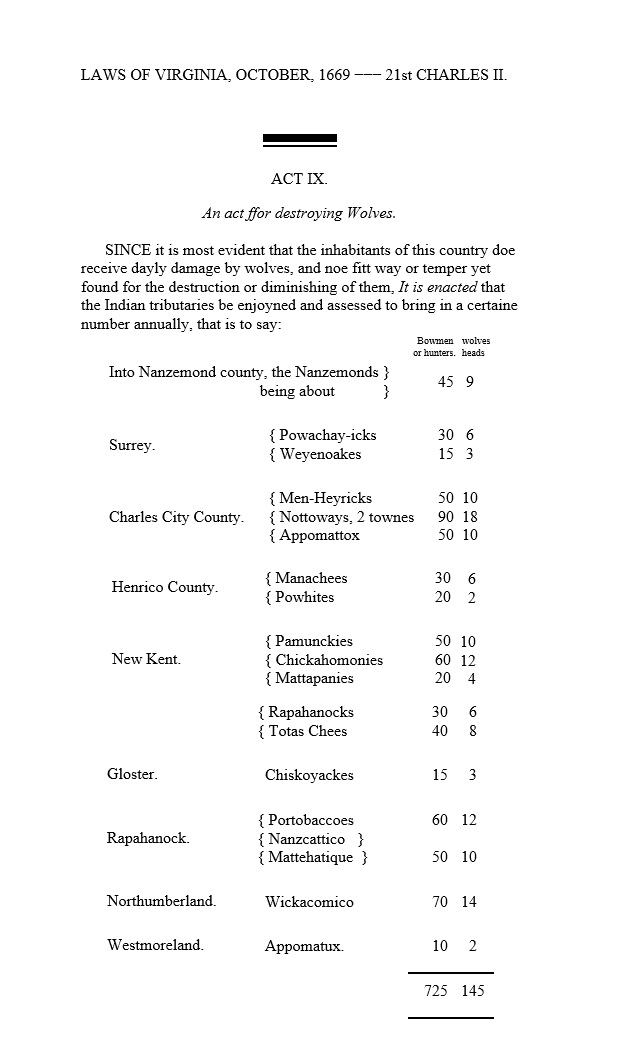

The Meherrin were reported as having 50 bowmen in Charles City County (which then

encompassed much of Southside Virginia) in 1669, or 185 people.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 72)

1669

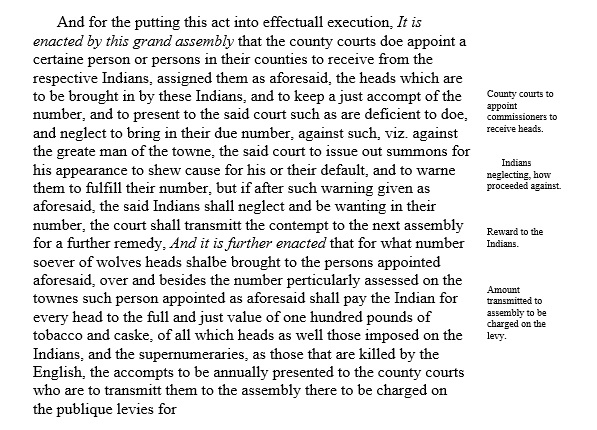

Oct 1669, An Act for Destroying wolves, lists 50 Meherrin Bowmen/Hunters having taken 10 Wolves.

1670

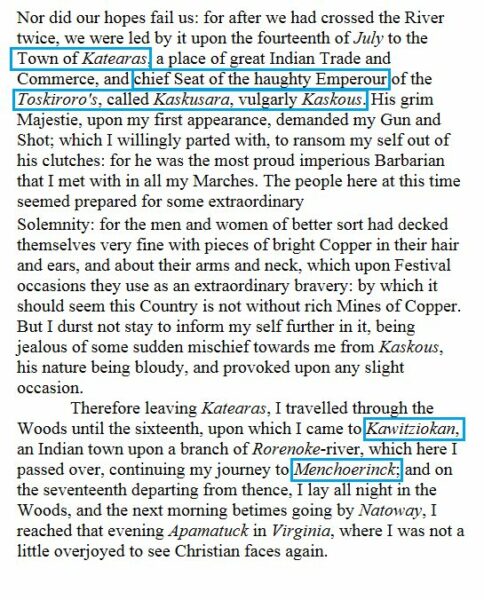

Lederer passed through their town without comment (Lederer 1958:33) This town (called “Menchoerinck” in the text and “Mendaerink” on map) appears on Lederer’s map. The Meherrin were reported as having 50 bowmen in Charles City County (which then

encompassed much of Southside Virginia) in 1669, or 185 people.

1670

Smallpox epidemic swept Meherrin communities.

1670

Deposition of Robert Bolling.

“… And that at the same time [ca. 1670] the Meherin Indians lived upon Meherin River; some of them at Cowinchahawkon, and the others at Unote; and there they continued to Live till about the year one thousand six hundred and eighty, or Longer, as the Deponent believes, but he cannot particularly remember the time of their Removal.”

Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (Standard, ed.) VII(4), 1900: 340-341. 1707

1670

Estimates of pre-contact population levels for any Native American group are extremely

difficult to calculate and bound to be fraught with controversy. “Censuses” of native populations

appear in colonial papers and miscellaneous accounts which shed light on historic populations.

These are usually expressed in numbers of “bowmen” or men eligible to tight. Since Mook

(1944), it has been accepted practice by ethnohistorians to calculate the entire population using

a 3.3 or 3.5 ratio to the bowmen count (Binford 1964). The earliest of these counts we have for

the Meherrin is 1670 (Stanard 1907:289) and it reports 50 bowmen, or a population of 175.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 32)

1670

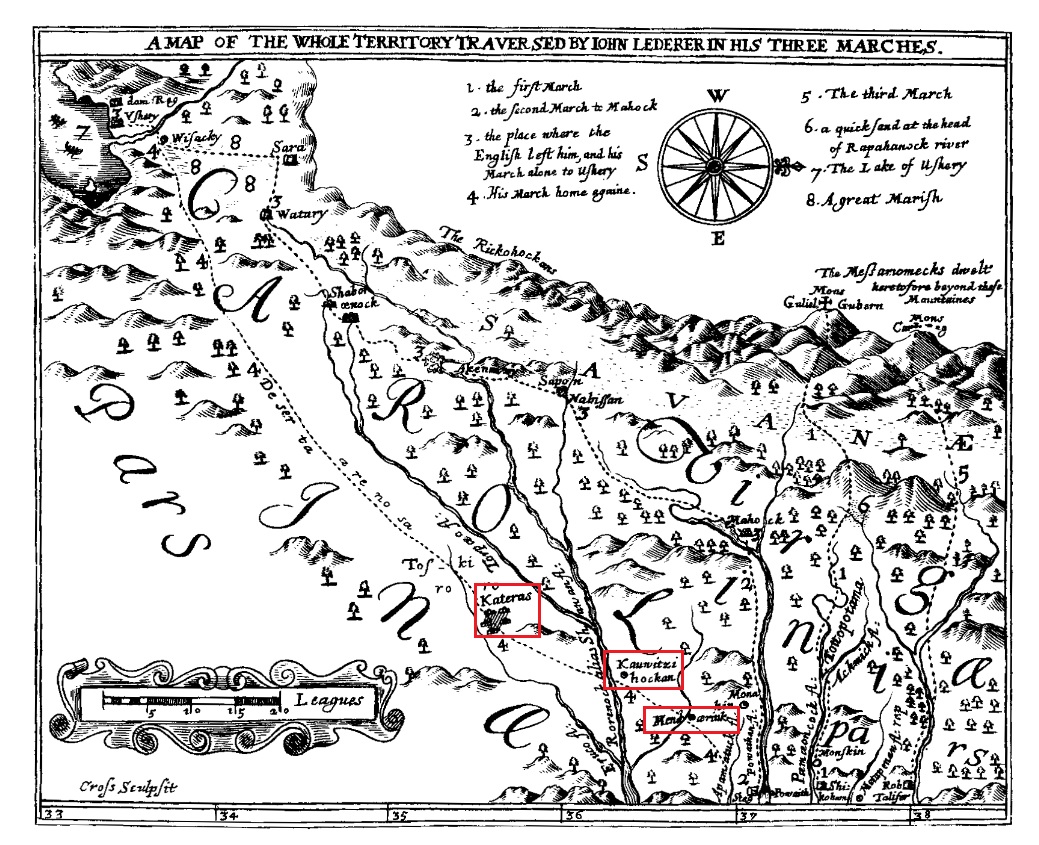

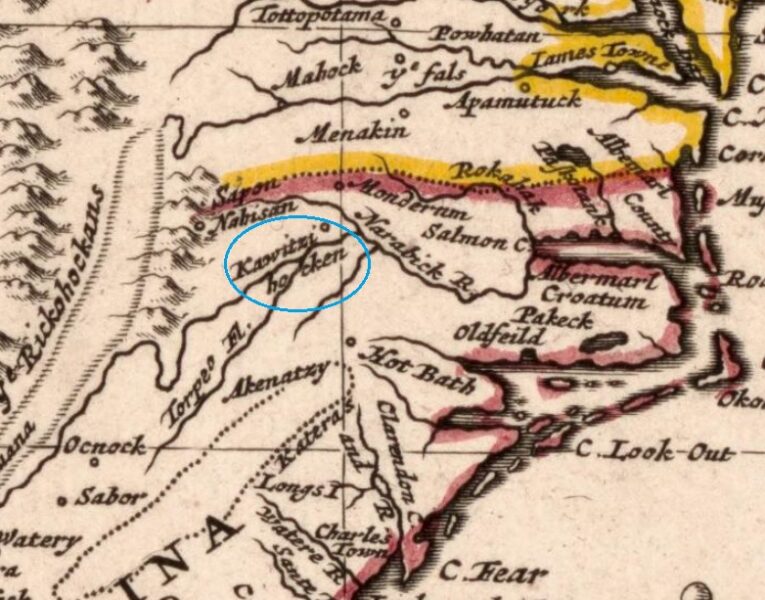

July 16, 1670 John Lederer arrives in the Meherrin town of Kawitziokan (Kauwitzihocken, Cowinchahawkon).

1670

July 17, 1670 John Lederer arrives in the Meherrin town of Menchooerink (Maherineck).

1670

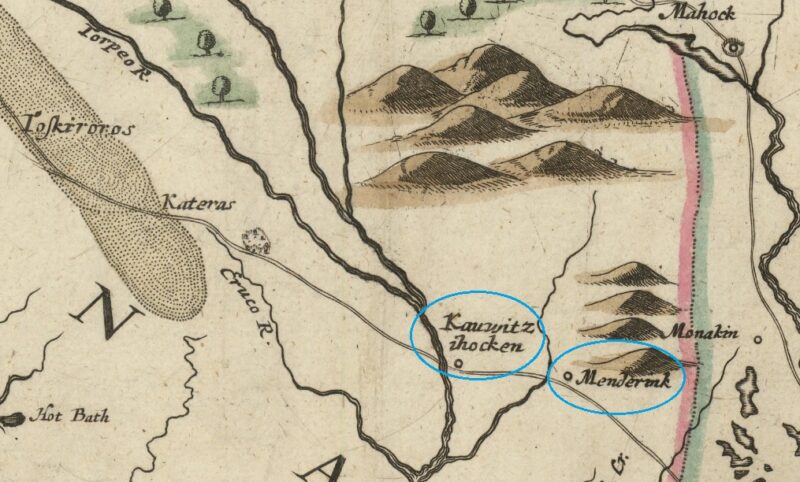

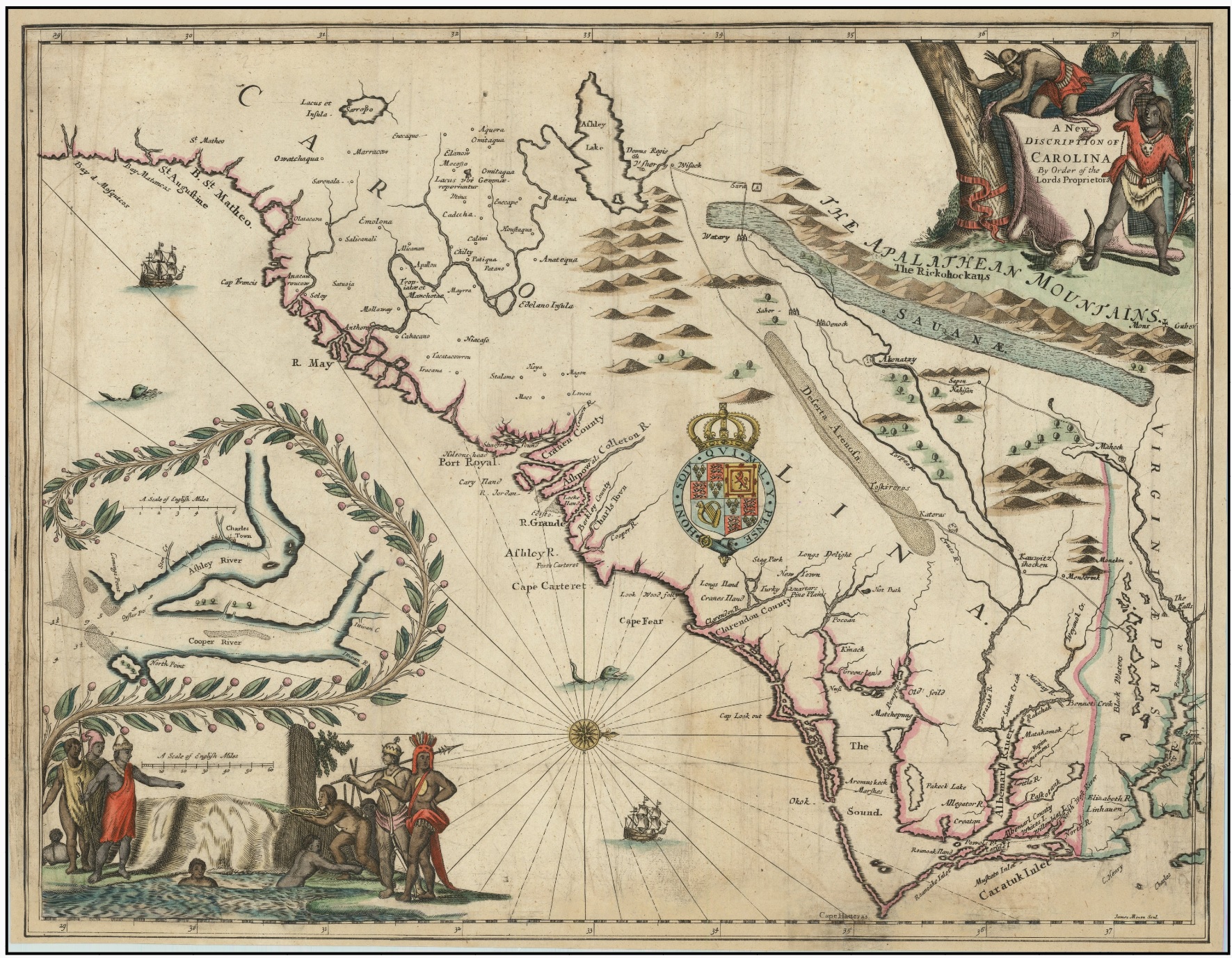

John Lederer Map

1671

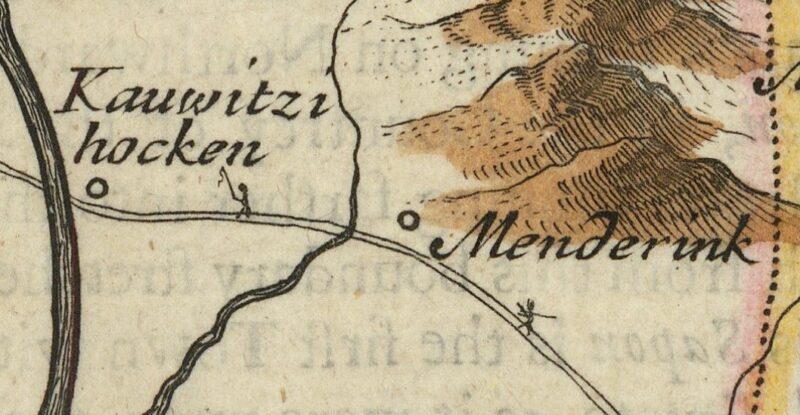

1670 Map. A new description of Carolina by the order of the Lords Proprietors. Created by John Ogilby and James Moxon.

This map shows the locations of two Meherrin villages/towns, these are listed on this map as Kauwitzihocken and Menderink.

1673

1673 Map. A new description of Carolina by the order of the Lords Proprietors. Created by John Ogilby and James Moxon.

1675

Meherrins provided a safe haven for the Conestoga/ Susquehanna who were fleeing Nathaniel Bacon and his militia. (Frantz, John B. Bacon’s Rebellion: Prologue to the Revolution? 1969)\

1676

1676 Map. A New Description of Carolina. John Speed.

This map shows the locations of two Meherrin villages/towns, these are listed on this map as Kauwitzihocken and Menderink

1677

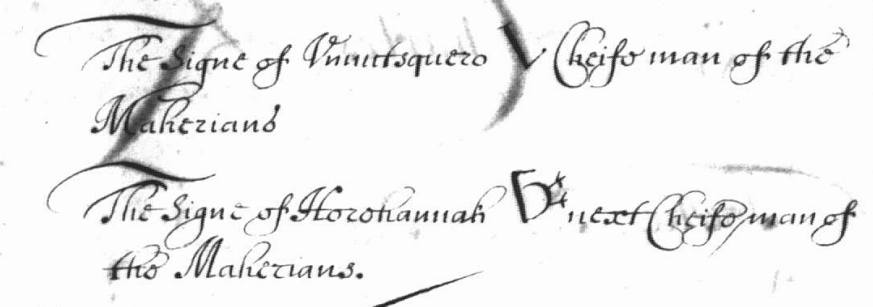

The Meherrins and Virginia colony had signed a treaty which outlined the boundaries of Meherrin territory and brought the Meherrins under their jurisdiction. At this time North Carolina was also claiming Meherrin territory. The two chiefs that signed the “Treaty of Middle Plantation” were named Ununtequero, “Chiefman” and Harehannah, “Next Chiefman. Their signature symbols are shown above, in a section of the original treaty document. The Harehannah’s resembles a snipe.

1677

Ununtequero, “King” of the Meherrin, signed a 1680 second version of the 1677 treaty; he was joined by Harehannah, the Meherrins’ “second chief.”

Virginia Magazine of History & Biography XIV (Stanard, ed.), Ja uary 1907, No. 3: 287-296. Treaty of May 29 ,1677 (1680).

1677

Deposition of Thomas Wynn [Meherrin Interpreter].

“That about thirty years ago [ca. 1677] the Meherrin Indians Lived part at Cowonchahawkon and parte at Unote; and about two and twenty years ago [ca. 1685] they settled their chief Town at the mouth of the River where they now live. That about fifteen years ago this Deponent having some Discourse with the old Meherin Indians, they told him that Waynoke creek lay to the Southward of Meherrin River, about Eight or Tenn miles from the present Meherrin Town…”

Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (Stanard, ed.) VII(4), 1900: 342. November 12,1707

1680

Between April and June of 1680 Chief Ununtequero and next Chief Harehannah signed the second version of the

Treaty of Middle Plantation. This treaty outlined the boundaries of Meherrin territory

and brought the Meherrin under the jurisdiction of Virginia. At this time North Carolina

was also claiming Meherrin territory

1680

Meherrins abandoned Cowonchahawkon near Emporia, Virginia after as a result of the Treaty of Middle Plantation” which was really an effort to subjegate the Meherrin (and other Indian) people under the Crown of England. Abandoning Cowonchahawkon was a strategic move on the part of Meherrins to avoid conflict with Colonists.

1681

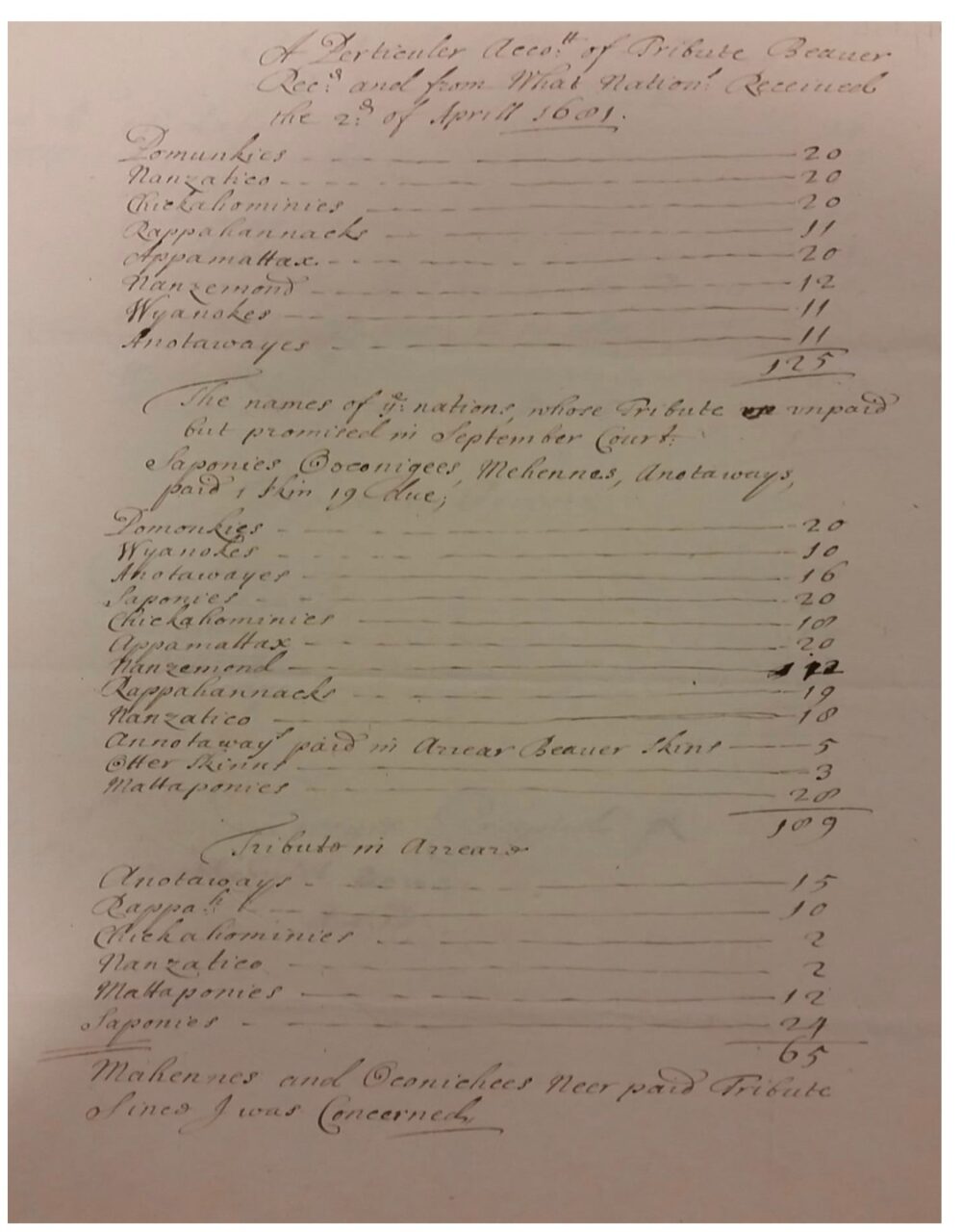

Nathaniel Bacon’s List of Tributary payments for 1681. Blathwayt Papers, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

States on the bottom that the Meherrin didn’t pay tribute.

Before 1683

The Meherrin reoccupied the Unote site at some point and remained there until

the mid-1680s.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 74)

1683

All the accounts agree on one important fact: the Meherrin had abandoned the

two old towns of Cowinchahawkon and Unote between 1683 and 1685. No reason is given.

They then settled at a place downstream, probably near present-day Boykins, Virginia, which they called Tawarra.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 74)

1680-1690

The Village at Tartara Creek was founded by Meherrins, at present-day Boykins, Virginia. This area was settled by the Meherrin to isolate themselves from the Colonials. This area was not inhabited by Whites at the time.

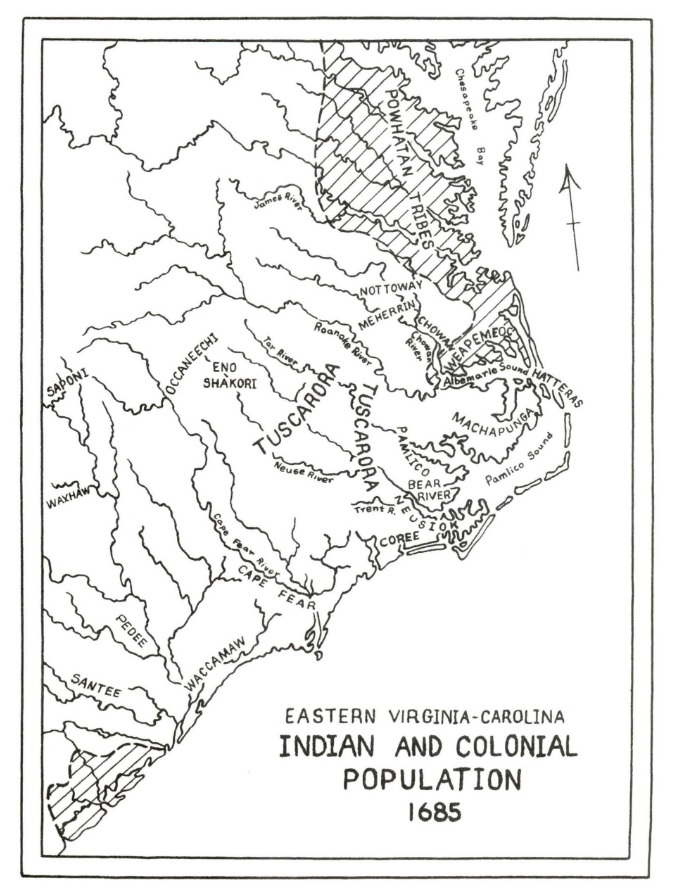

1685

1686

…the Nation of Indiana Called the Meherins hath Deserted their former place of Residence, or Habitations, and hath lately Seated themselves on the North Side of the Blackwater, Contrary to the Limitts, and Bounds in former ycares Sett unto the Indians, and to which the Meherins never made any pretention unto, and being Come upon the Skirts, and Borders of the English Plantations they are Injurious to them in their Stocks, by private Killing, and destroying of them, and not only soe, but by their Insolent Carriadge, terrifye, and affright

the Inhabitants… (Mcllwaine, Vol. 1:83-84, April 29, 1687).

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 76)

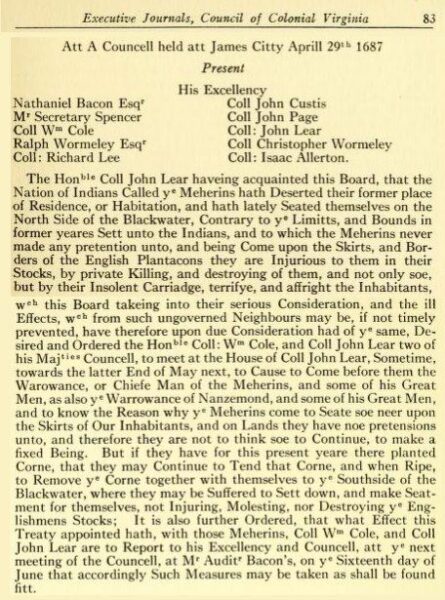

1687

[Marauding Meherrins on the north side of the Blackwater – ordered to move south]

“The Honorable Coll John Lear haveing acquainted this Board, that the Nation of Indians Called the Meherins hath deserted their former place of Residence, or Habitations, and hath lately seated themselves on the North Side of the Blackwater, contrary to the limits, and bounds in former years set unto the Indians, and to which the Meherins never made any pretention unto, and being come upon the skirts, and borders of the English plantations they are Injurious to them in their stocks, by private killing, and destroying of them, and not only soe, but by their Insolent carriadge, tenifye, and affright the Inhabitants, which this board taking into their serious Consideration, and the ill rffects, which from such ungoverned neighbours may be, if not timely prevented, have therefore upon due consideration had of the same, desired and ordered the honorable Coll: William Cole, and Coll John Lear two of his Majesties councel, to meet at the House of Coll John Lear, Sometime towards the latter End of May next, to cause to come before them the Warowance, or Chiefe Man of the Meherins, and some of his Great Men, as also the Warrowance of Nanzemond, and some of his Great Men and to know the reason why the Meherins come to seate soe neer upon the Skirts of Our Inhabitants, and on Lands they have noe pretensions unto, and therefore they are not to think soe to continue, to make a fixed Being. But if they have for this present yeare there planted Come, that they may continue to tend that come, and when ripe, to remove the come together with themselves to the southside of the Blackwater, where they may be suffered to sett down, and make seatment for themselves, no Injuring, molesting, nor destroying the Englishmens Stocks; It is also further ordered, that what effect this treaty appointed hath, with those Meherins, Coll William Cole, and Coll John Lear are to Report to his Excellency and Councell, att the next meeting of the Councell, at Mr. Auditor Bacon’s on the Sixteenth day of June that accordingly Such Measures may be taken as shall be found fit

Virginia Executive Journal of Council (Mcllwaine), I: 83-84; April 29, 1687

1688

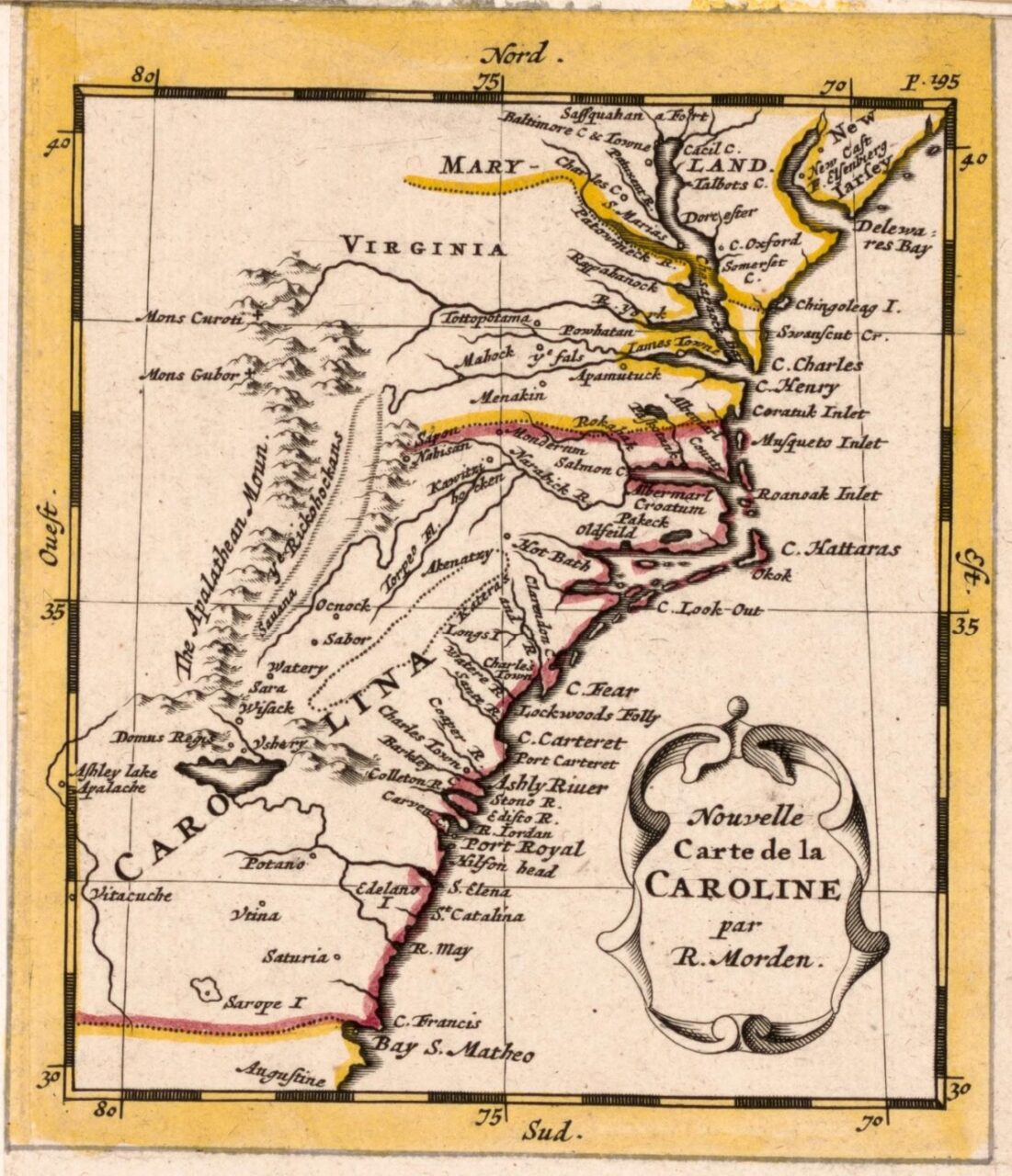

1688 Map. Nouvelle carte de la Caroline. Robert Morden.

The Meherrin village of Kawitzihocken (Kauwitzihocken, Cowinchahawkon), is listed on this map.

1691

In 1691 Daniel Pugh, a settler in Nansemond County (present-day city of Suffolk), abducted four Tuscarora Indians and sold them as slaves in the West Indies, action for which government officials attempted to prosecute him. Making use of the legal system, eight or ten Tuscarora great men and a Meherrin testified about the event and one witness said that the missing men had been transported to Barbados.

COLONIAL (National Park Service)

A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

CHAPTER 4:

Narrative History

Martha W. McCartney

1691

In 1691 several Surry County citizens requested compensation for transporting Indians to Jamestown and back, so that they could pay their tribute. Nicholas Witherington testified that on April 25th he had brought six Meherrin Indians to the capital city and two days later he had taken six Nansemonds there.

COLONIAL (National Park Service)

A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

CHAPTER 4:

Narrative History

Martha W. McCartney

1691

“… the begining of this Month Eight or ten of the Kings and Great men of the Tuskaroro Indians Complained to him that two of their Indians were wanting, and they Imagined the English had killed them, but a Maherin Indian being present told them that Danll Pugh of Nansimond County in this Government had Sent them to Barbados, on which they threatnd Revenge”

Virginia Executive Journal o f Council (Mcllwaine) I: 146-147. Jan u ary 26, 1691

1692

In 1692 Captain Thomas Swann testified that his ferryman had transported nine Weyanoke Indians to and from Jamestown and had made round trips to the capital with ten Appomattocks and five Meherrin.

COLONIAL (National Park Service)

A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

CHAPTER 4:

Narrative History

Martha W. McCartney

1696

Meherrins began moving down the Meherrin River into the area of present-day Murfreesburough, in Hertford County, North Carolina near “Meherrin Neck” (today known as Manley’s Neck). (This area was part of Virginia colony until 1728 when it became North Carolina territory) Meherrins are noted at “Meherrin Indian Town” on this section of a 1711 map.

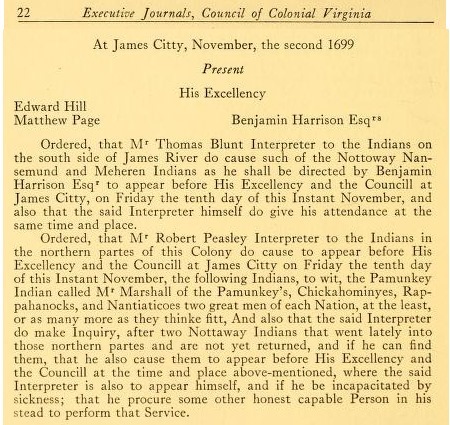

1699

“Ordered that Mr. Thomas Blunt Interpreter to the Indians on the south side of James River do

cause such of the Nottoway Nansemund and Meheren Indians as he shall be directed by Benjamin Harrison Esqr to appear before His Excellency and the Councill at James Citty, on Friday the tenth day of this Instant November, and also that the said Interpreter himself do give his attendance at the same time and place. ”

Virginia Executive Journal of Council (Mcllwaine) II: 22. November 2, 1699

1699

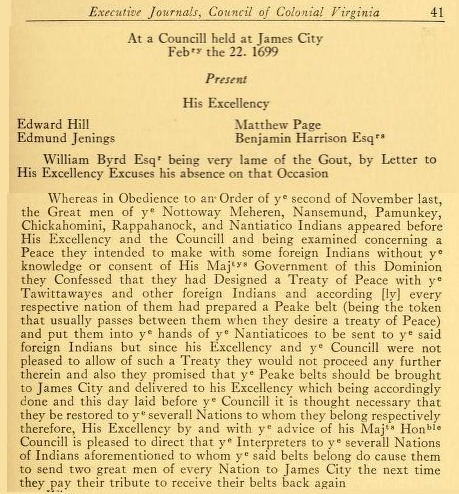

Feb 22, 1699

1699

Virginia ordered its official interpreters to interfere with peace treaties between the Indians residing in the Virginia Colony (including Meherrin) and with other Indian nations seeking peace with Virginia Nations. They ordered Indian “Great Men” to turn their peace treaty belts (Wampum belts) over to the colony, rather than to present them to one another, directly interfering in peace agreements and soverign affairs. The colony was fearful that the First Nations would form a powerful alliance that could threaten the colony’s land-grabbing and expansion.

“Whereas in Obedience to an Order of ye second of November last, the Great Men of ye Nottoway, Meheren, Nansemund, Pamunkey, Chickahomini, Rappahanock, and Nantiatico Indians appeared before His Excellency and The Council and being examined concerning a Peace they intended to make with some Foreign Indians without ye knowledge or consent of His Majesty’s Government of this Dominion they Confessed that they had Designed a Treaty of Peace with ye Tawittawayes and other Foreign Indians and according [ly] every respective nation of them had prepared a Peake Belt (being a token that usually passed between them when they desired a Treaty of Peace ) and put them into the hands of ye Nantiaticoes to be sent to ye said Foreign Indians but since His Excellency and ye Council were not pleased to allow of such a Treaty they would not proceed any further therein and also they promised that ye Peace Belts should be brought to James City and delivered to His Excellency which being accordingly done and this day laid before ye said Council it is thought necessary they be restored to ye severall Nations to whom they belong respectively therefore, His Excellency by and with ye advice of His Majesties Honorable Council is pleased to direct that ye interpreters to ye severall Nations of Indians aforementioned to whom ye said belts belong do cause them to send two Great Men of every Nation to James City the next time they pay their Tribute to receive their belts back again.

“Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia , Aug. 3, 1699- April 27,1705- Vol. II ,p.2 & p.41 ( Library of Virginia 1928)

1699

Nov 2, 1699