Return to Meherrin Neck

“Return to Meherrin Neck” represents a long-held vision of our community, one that envisions the restoration of our ancestral lands to our people. It is a dream that has been passed down through generations, a dream of reclaiming the land where our forebears are laid to rest and where we can once again hold sacred ceremonies. With your assistance, we can work towards redressing past injustices and ensuring that the next seven generations can walk the same land, knowing that we had their interests in mind when we first envisioned this return to Meherrin Neck.

Interested in helping, please visit our donation portal

Going forward

We have initiated collaborative efforts with private landowners, companies, organizations, and donors to facilitate the repurchase of some of our ancestral lands. These lands were never ceded nor legally signed away and hold significant cultural and historical value for our community. With your support, we can continue to move forward with this vital work of reclaiming what is rightfully ours.

In addition to our efforts with private entities, we are also seeking to collaborate with the State of North Carolina to regain stewardship of some of our traditional lands. These lands are currently under the state’s ownership and title, yet we have never legally ceded or signed them away. By working together with the state, we hope to secure the return of these lands to our Nation, allowing us to safeguard our cultural heritage and continue our ancestral practices for generations to come.

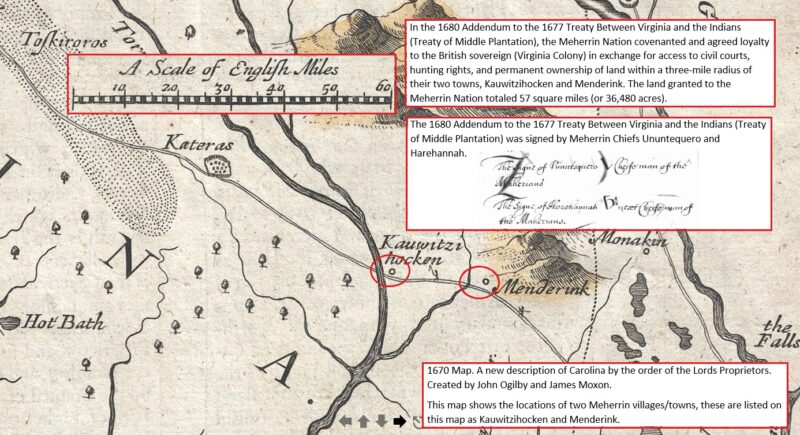

1680 Addendum to the 1677 Treaty Between Virginia and the Indians (Treaty of Middle Plantation).

In 1680, the Meherrin Nation signed an Addendum to the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation with the British Sovereign (Virginia Colony), which established two reservations – Kauwitzihocken and Menderink.

In signing this Treaty, the Meherrin were granted access to civil courts, as well as hunting rights and permanent ownership of land within these two tracts of land that totaled 36,295.6 acres (56.72 square miles).

1677 Treaty Between Virginia and the Indians (Treaty of Middle Plantation).

1680 Addendum to the 1677 Treaty Between Virginia and the Indians (Treaty of Middle Plantation).

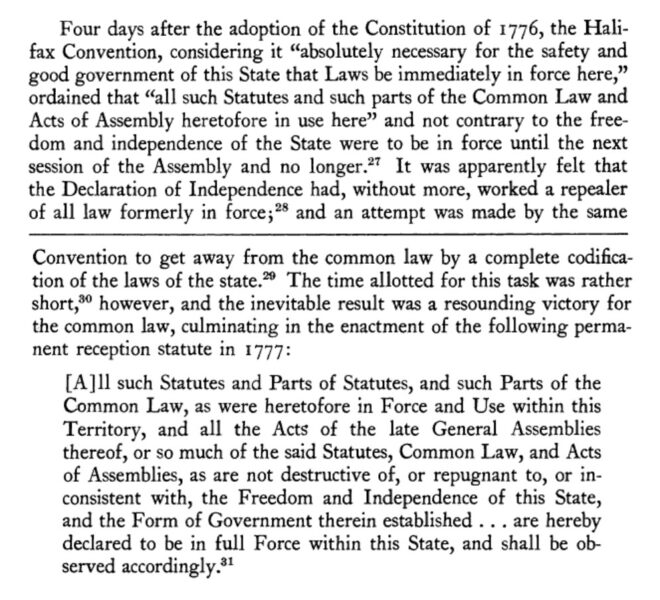

Note: When the United States achieved independence from Great Britain, it adopted all previous treaties made by the British government that were still in force and not contrary to the new nation’s laws or policies. This principle is known as the “doctrine of continuity,” which means that international agreements entered into by a predecessor state remain binding on the successor state.

Historically, treaties made between the British Crown and Virginia Indian tribes were inherited by the United States government upon independence. In adherence to these treaties, the United States government made an agreement to honor them, and they remain legally binding to this day.

Doctrine of Continuity

The doctrine of continuity is a legal principle that recognizes the continued validity and enforceability of treaties and agreements made by previous governments. It has been recognized by U.S. courts as well as international courts and tribunals.

In the United States, the Supreme Court has upheld the doctrine of continuity in a number of cases, including Worcester v. Georgia (1832) and United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians (1980).

One notable example is the case of Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. County of Oneida (1985), where the court ruled that the Oneida Indian Nation maintained its aboriginal title to certain lands in New York state, despite centuries of non-Indian use and settlement. The court held that the doctrine of continuity applied, and that the Oneida Indian Nation had not been divested of its title through the actions of colonial or state governments.

These cases affirmed the continuing validity of treaties made between the United States government and Native American tribes, even after the passage of subsequent laws or changes in government policy.

1705

In 1705 the Colonial Government of Virginia established the second reservation in what is now North Carolina, for Meherrins who were living at Meherrin Neck (Maney’s Neck).

Three-mile round reservation to be set out for Meherrin between the Meherrin and Nottoway Rivers.] “Resolved That The Bounds of The Maherin Indians Land be Laid out as Followed! (viz.) a Streight Line Shall be Run up The Middle of The Neck between Maherin River and Nottoway River from The Mouths of the Said Rivers so far as will Include between that Line and Maherin River So much Land as will be Equal in Quantity to a Circle of Three Miles Round Their Town. This tract of land totaled 18,146.8 acres (28.36 square miles).

The Meherrin were assigned this reservation (Meherrin Neck) by the Virginia Assembly in an area that was subject to a boundary dispute between Virginia and North Carolina. As a result, the question of which colony had a say in Meherrin affairs became a part of the borderline dispute.

1707

In 1707, the Virginia Council of State supported the Meherrin against pressures from the North Carolina government over control of the Meherrin land and whether the Tribe should pay tribute to the colony.

1715

In 1715, an agreement was made on the general boundary line, although the details were to be agreed upon following a survey. If confirmed, the Meherrin would now be on the North Carolina side of the borderline.

1726 (1)

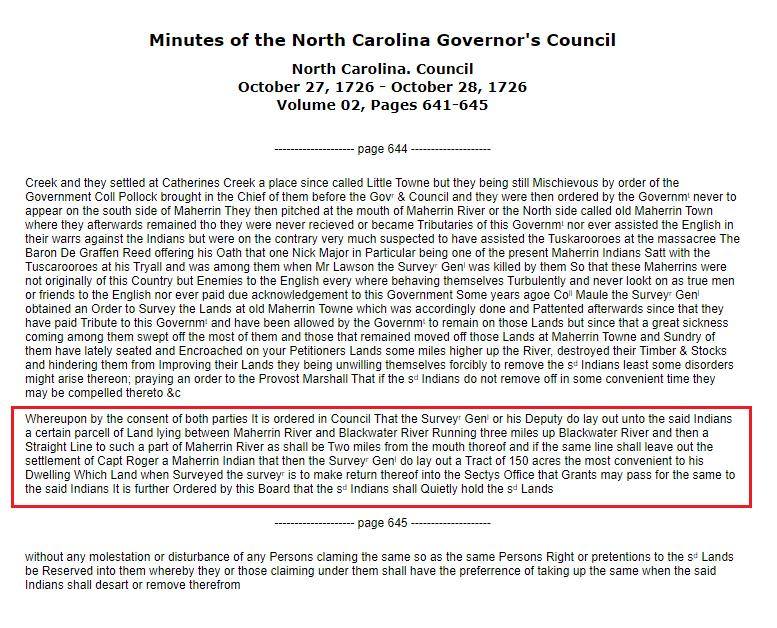

To protect their lands from the claims of settlers, the Meherrin successfully petitioned the North Carolina government to grant them a reservation.

1726 (2)

In 1726 the Meherrin were assigned to a new reservation tract by the North Carolina General Assembly, this would be their fourth assigned reservation, and third one in North Carolina. This reservation greatly reduced the size of the reservation established by the Virginia Colony in 1705 to a six-mile reservation in the land called “Meherrin Neck” which later became known as Maney’s Neck.

It is further Ordered by this Board that the said Indians shall Quietly hold the said Lands without any molestation or disturbance of any Persons claiming the same so as the same Persons Right or pretentions to the said Lands be Reserved unto them Whereby they or those claiming under them shall have the preferrence of taking up the same when the said Indians shall desart or remove therefrom.

(The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Second Series – Volume VII – Records of the Executive Council – 1674-1734.)

1728

After a joint surveying expedition mounted by both colonies in 1728, the North Carolina-Virginia border was finalized.

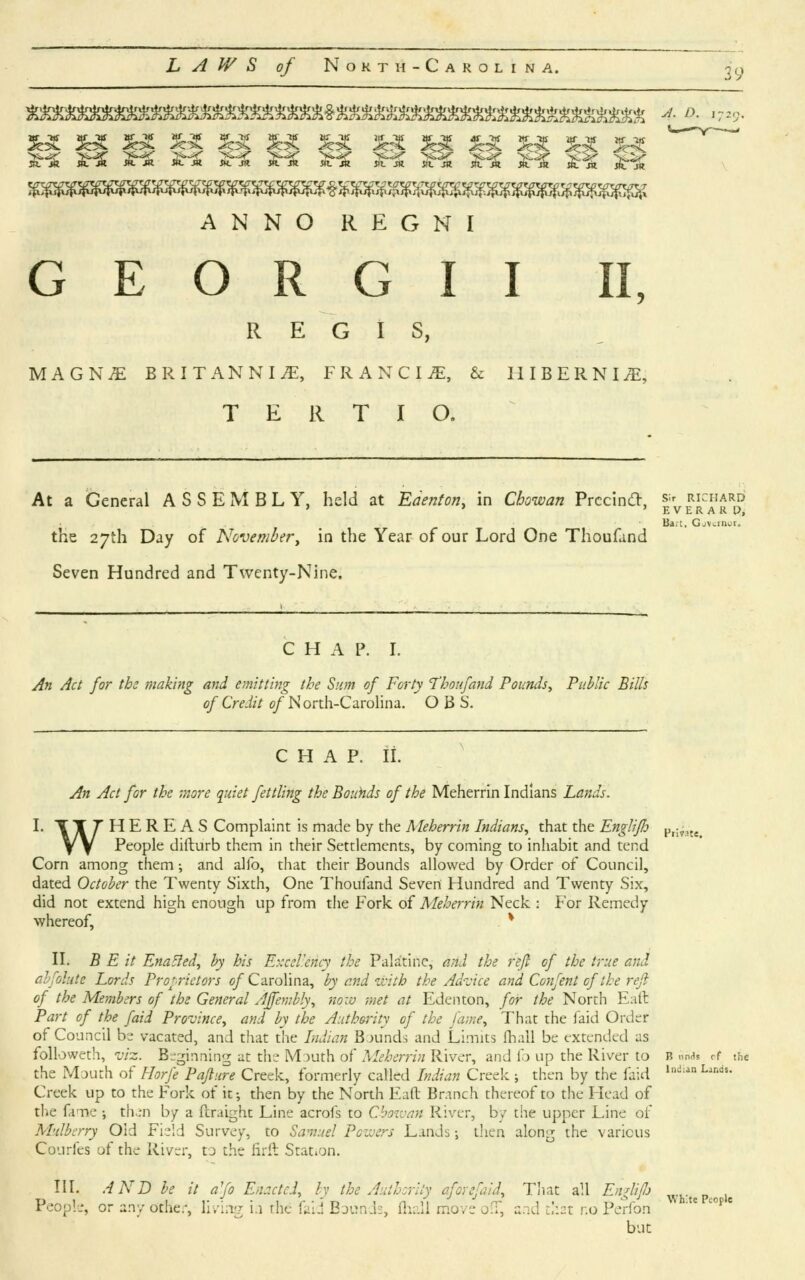

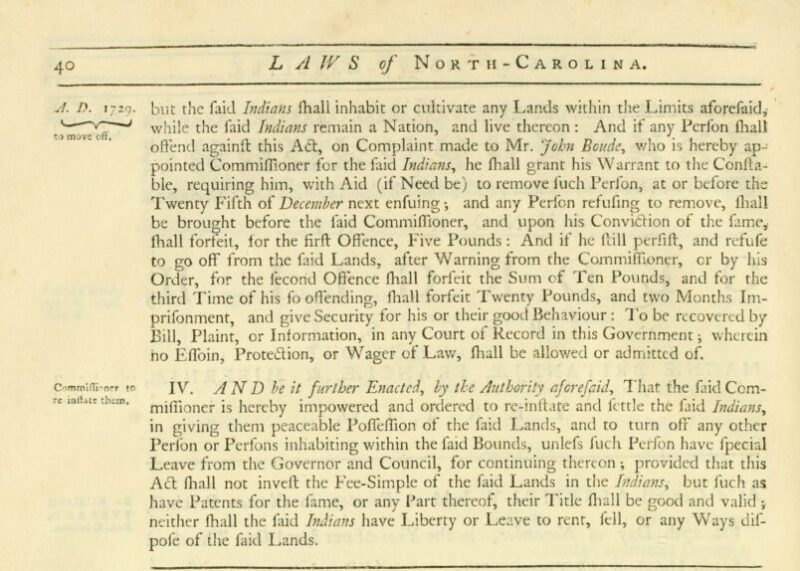

1729

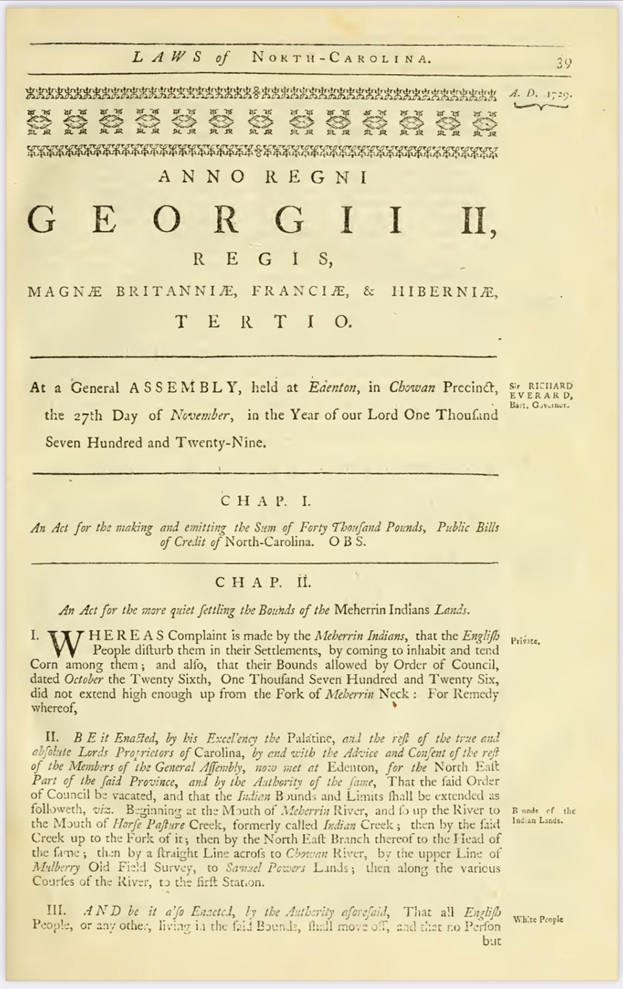

The Meherrin became tributaries of North Carolina in 1729 through an act of the colonial legislature.

1729 (2)

In 1729 “An Act for the More Quiet Settling the Bounds of the Meherrin Indian Lands” a new reservation was established at the confluence of the Chowan and Meherrin rivers. This was an expansion of the 1726 reservation.

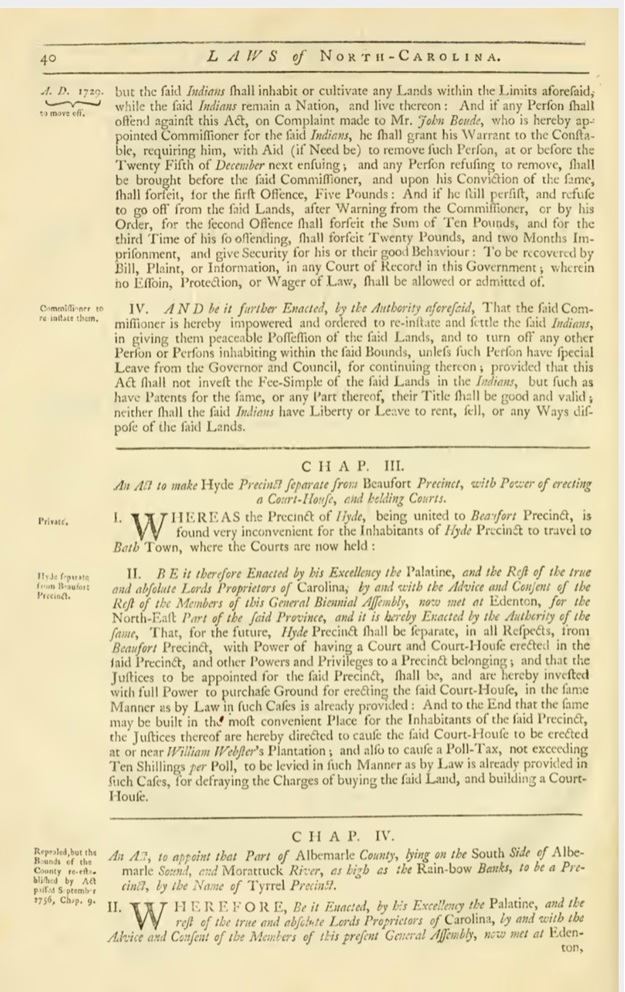

North Carolina. General Assembly November 27, 1729 Volume 25, Pages 211-213

1730

Virginia acknowledged that the Meherrin actually lived in North Carolina.

The Indians tributary to this Government are reduced to a small number the remains of the Maherin and Nansemond Indians are by running the Boundary fallen within the limits of North Carolina…

(B.P.R.O.B.T. Virginia. Vol. 19. R. 127, September 14, 1730).

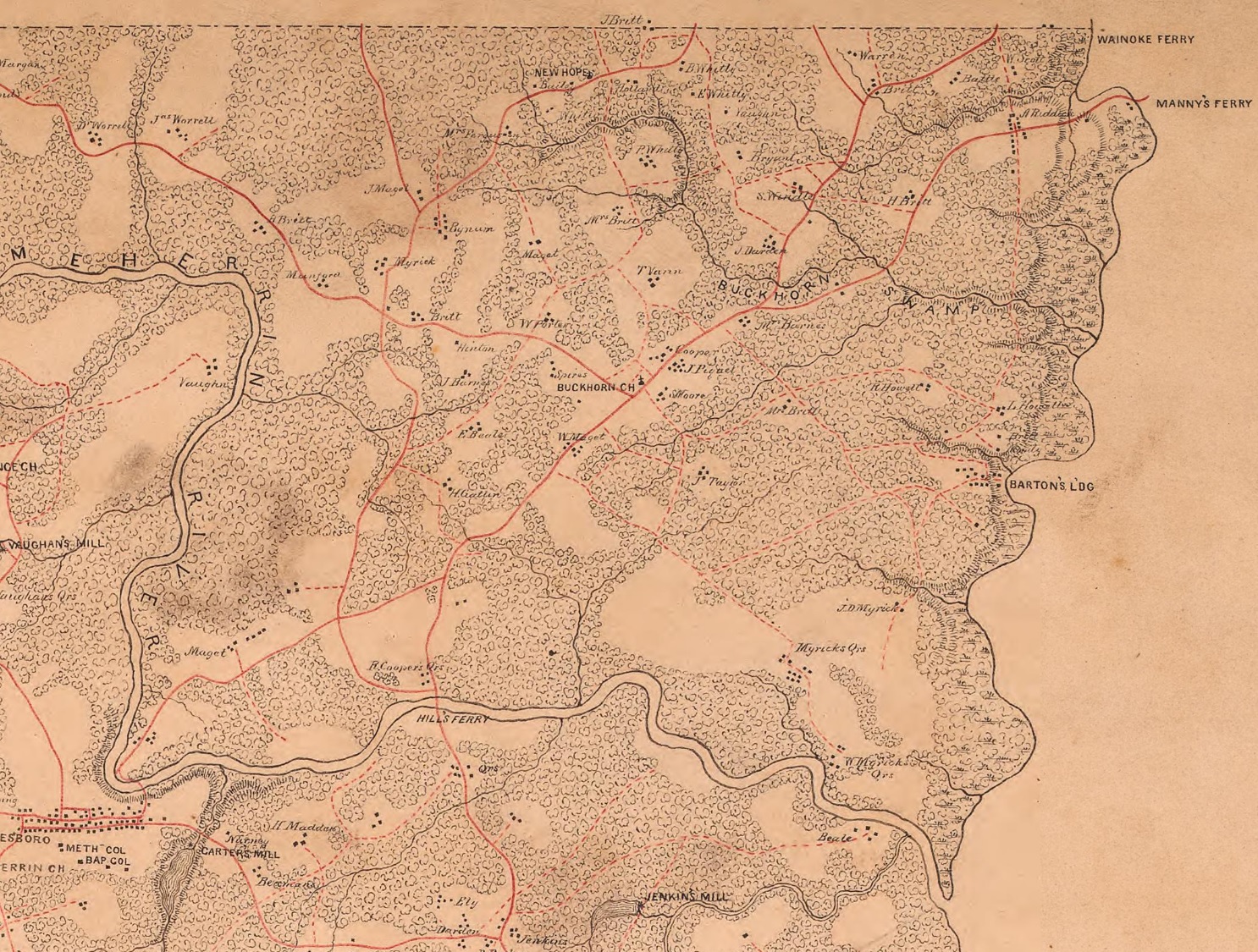

1733

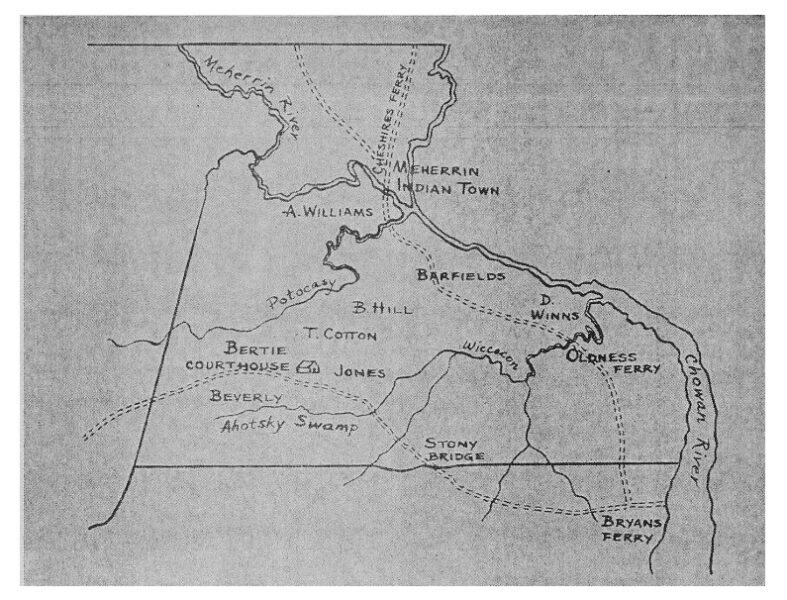

Meherrin Indian Town located on this 1733 map in present day Maneys Neck, North Carolina.

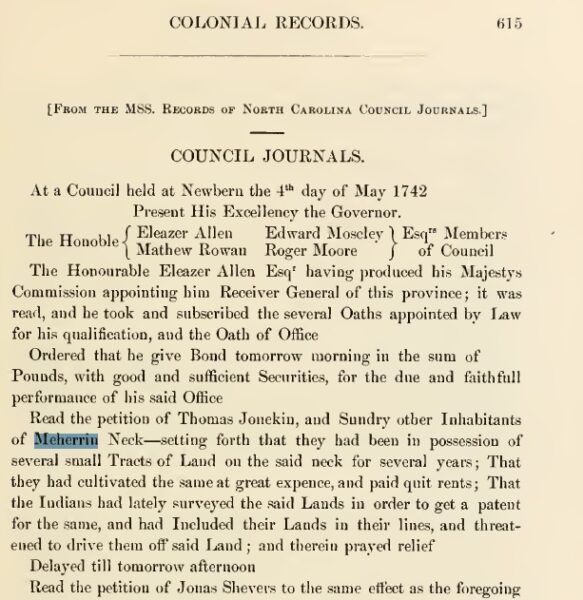

1742 (1)

Read the petition of Thomas Jonekin, and Sundry other Inhabitants of Meherrin Neck – setting forth that they had been in possession of several small Tracts of Land on the said neck for several years; That they had cultivated the same at great expence, and paid quit rents; That the Indians had lately surveyed the said Lands in order to get a patent for the same, and had Included their Lands in the lines, and threatened to drive them off said Land; and therein prayed relief

Delayed till tomorrow afternoon

Read the petition of Jonas Shevers [Chavis?] to the same effect as the foregoing

Referred the Consideration thereof till tomorrow”

North Carolina Colonial Records (Saunders) IV: 615-616. M ay 4, 1742.

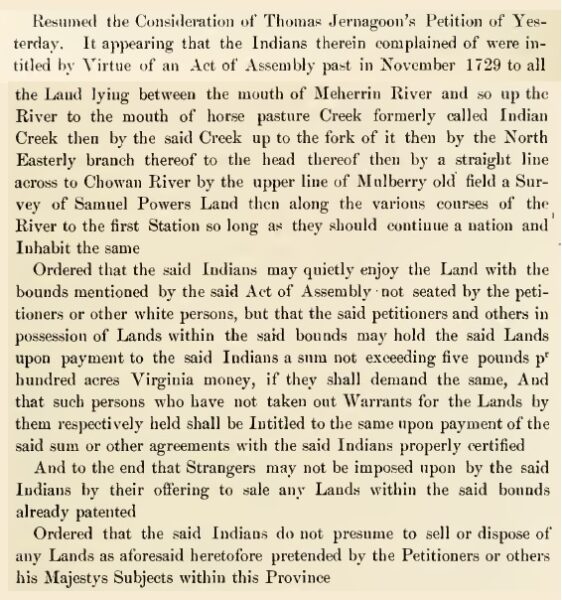

1742 (2)

Council held at Newberne.

Resumed the Consideration of Thomas Jemagoon’s Petition Yesterday. It appearing that the Indians therein complained of were intitled by Virtue of an Act of Assembly past in November 1729 to all the Land lying between the mouth of the Meherrin River and so up the River to the mouth of horse pasture Creek formerly called Indian Creek then by the said Creek up to the fork of it then by the North Easterly branch thereof to the head thereof then by a straight line across to Chowan River by the upper line of Mulberry old field a Survey of Samuel Powers Land then along the various courses of the River to the first Station so long as they should continue a nation and Inhabit the same

Ordered that the said Indians may quietly enjoy the Land with the bounds mentioned by the said Act of Assembly not seated by the petitioners or other white persons, but that the said petitioners and others in possession of Lands within the said bounds may hold the said Lands upon payment to the said Indians a sum not exceeding five pounds p r hundred acres Virginia money, if they shall demand the same, And that such persons who have not taken out Warrants for the Lands by them respectively held shall be Intitled to the same upon payment of the said sum or other agreements with the said Indians properly certified. And to the end that Strangers may not be imposed upon by the said Indians by their offering to sale any Lands within the said bounds already patented. Ordered that the said Indians do not presume to sell or dispose of any Lands as aforesaid heretofore pretended by the Petitioners or others his Majestys Subjects within this Province…

North Carolina Colonial Records (Saunders) IV: 616-617. May 5, 1742.

1742 (3)

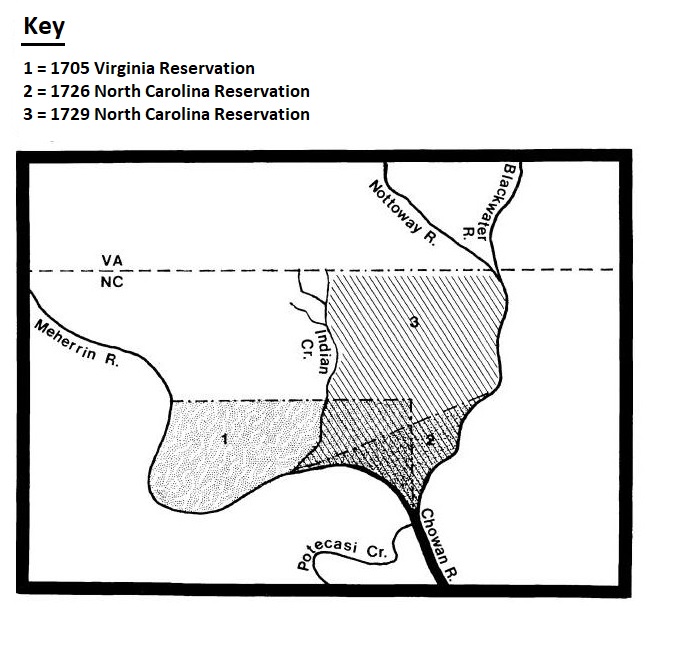

We know that the Meherrin “quietly enjoyed” their reservation until 1742, when Thomas Jemagoon (Jonekin) and “sundry inhabitants” complained to the North Carolina council of Meherrin encroachments. The area under contention was the same northern section of Meherrin territory – around the branching of Indian/Horse Pasture Creek (also called Indian Swamp) – that had been contested with Maule and Gray in the 1720’s and had instigated the creation of the first North Carolina reservation. The Act of 1729 extended the reservation to include land in the neck south of Indian Creek. In 1739 and 1740, a slue of Bertie County deeds for tracts south of the creek passed between white men presuming title from earlier patents which should have been nullified by the 1729 Act.6 Figure 9 approximates the Meherrin’s three known “reservations” located on Meherrin Neck: the land granted by Virginia in 1705, the 1726 North Carolina bounds, and the 1729 extension.

The Jemagoon family purchased 575 acres from a Richard Holland which is described, “on Chowan River known by name Indian Town on SS Indian Creek” (Bertie County Deed Book C:100, also D:22). Jemagoon had to have been aware of the Meherrin claim on the property. It would appear that the Meherrin had a town site on this tract prior to 1728, but had since moved their main settlement back to the mouth of the Meherrin. Regardless, this land was included in the Act of 1729 and the Meherrin began to re-survey the bounds to assert their rights, raising Jemagoon’s alarm. He sent a petition to North Carolina’s council wherein it was reported that the Meherrin “threatened to drive them off the land” (Saunders, Vol. IV:615-616; May 4, 1742).7 The Meherrin still had some fight left in them.

The Council’s response gives us a clue to the mystery of how the Meherrin eventually

lost their reservation land. The council, while recognizing the Meherrin’s legal entitlement to the land, effectively revoked the Meherrin’s exclusive right to occupy and control the land.

Ordered that the said Indians may quietly enjoy the Land with the bounds mentioned by the said Act of Assembly not seated by the petitioners or other white persons, but that the said petitioners and others in possession of Lands within the said bounds may hold the said Lands upon payment to the said Indians a sum not exceeding five pounds pr hundred acres Virginia money… (Saunders, Vol. IV:616-617. May 5, 1742, Document B-73).

In other words, the Meherrin were forced to accept rent from the English squatters and had their rights limited to that land within the bounds not “not seated by the petitioners or other white persons.” The executive order is of dubious legality considering that the 1729 reservation bounds and conditions were set by an Act of Assembly. Even under colonial procedure it should have required a second Act of Assembly to amend the law which specifically prohibited the Meherrin from renting or leasing lands. The document is doubly of significance for specifying for the first time a white/Indian dichotomy. All previous references had been to “English or other Europeans.” An incipient redefinition of social relations into terms of race makes its appearance.

1746 (1)

The Meherrin persevered. Perceiving the split in government branches, they petitioned the Assembly directly in 1746. They complained not only of white intrusions (ignoring the order that they view the whites as tenants), but of their appointed commissioner, who had clearly failed to protect their interests. (Document B-74). The records indicate that a second bill for “quieting the possession of the Meherrin Indians” (ibid.) was passed, but unfortunately, we have no record of its content.

(The Secret History of the Meherrin page 108)

1746 (2)

House Minutes.

“The House met according to Adjournment. Read the Petition of the Meherin Indians, setting forth the hardships they labour under by reason of the white people intruding on their Possessions and also that the Commissioners appointed by an Act of the General Assembly to settle the said Indians in the quiet possession of their possessions, and praying relief thereon. On reading of which said Petition Mr. Benjamin Hill moved for leave to bring in a Bill pursuant to a prayer of the sd Petition. Ordered that he have leave & that he prepare & bring in the same.”

North Carolina Colonial Records (Saunders) IV: 820. June 17, 1746.

1746 (3)

North Carolina Colonial Records

Tuesday 17th June 1746. The House met according to Adjournment. Read the Petition of the Meherin Indians, setting forth the hardships they labour under by reason of the white people intruding on their Possessions and also that the Commissioners appointed by an Act of the General Assembly to settle the said Indians in the quiet possession of their possessions, and praying relief thereon.

(Colonial Native Dispossession of North Carolina Researched by: Baylus C. Brooks Research Assistant: Julie S. Brooks. Page 62)

1746 (4)

House Minutes.

“Received from the Council the following Bills (that is to say) The Militia Bill and the Bill for quieting the Possession of the Meherin Indians. Endorsed June 18th 1746 In the Upper House read the first time & passed.”

North Carolina Colonial Records (Saunders) IV: 822. June 18, 1746.

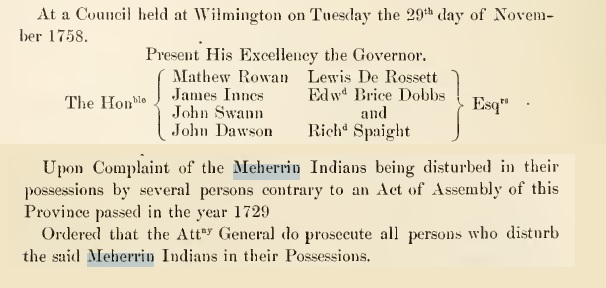

1758

In 1758, the North Carolina council passed a

resolution to help enforce the rights of the Meherrin:

Upon complaint of the Meherrin Indians being disturbed in their possession by several persons, contrary to act of 1729, Ordered that the Attorney General do prosecute all persons who disturb the said Meherrin Indians in their possessions

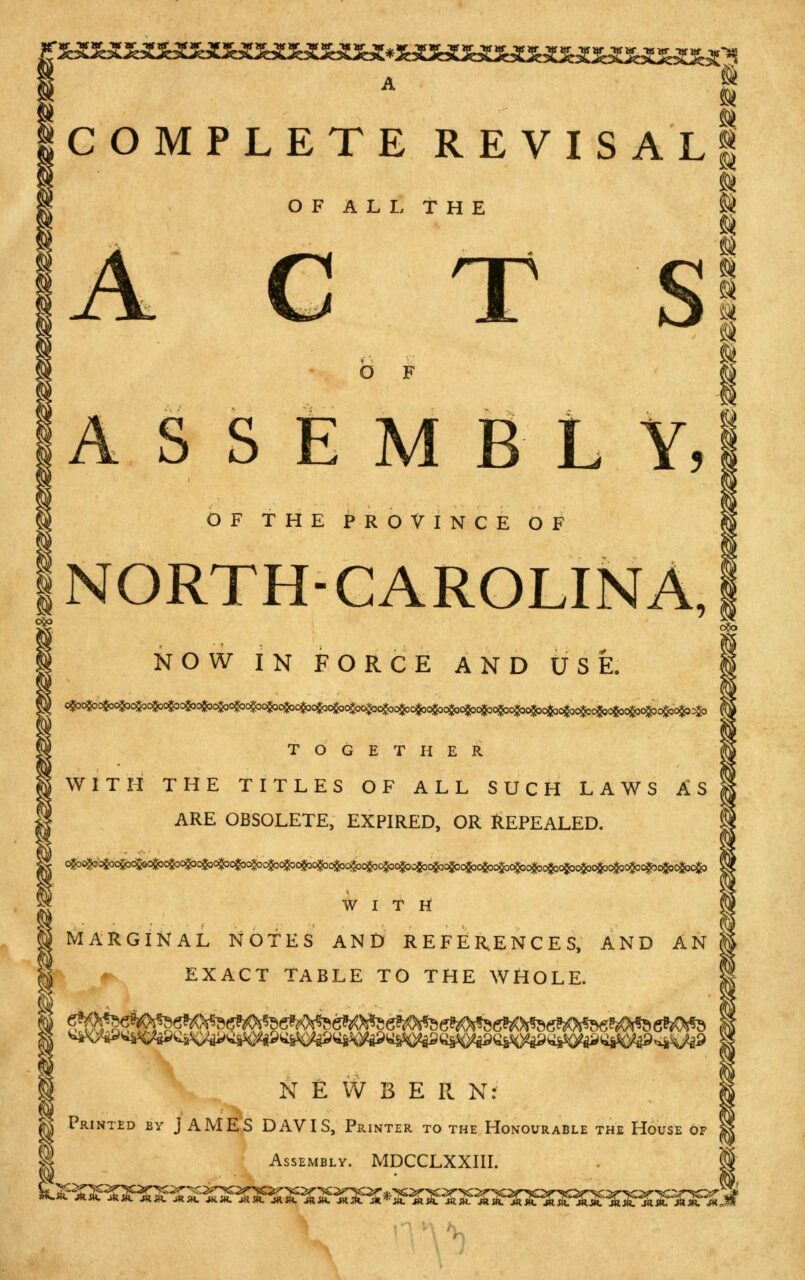

1773

A Complete Revisal of all the Acts of Assembly of the Province of North Carolina now in force and use.

Published by Newbern [N.C.] : Printed by James Davis, printer to the Honourable the House of Assembly., MDCCXXIII., 1773

Note: The acts that were included in the 1773 “A Complete Revisal of all the Acts of Assembly of the Province of North Carolina now in force and use” were in effect at the time of publication. The revisal was a compilation of all the laws that were in effect in the colony of North Carolina at that time, and it was intended to provide a comprehensive guide to the laws that governed the colony. The revisal was an important document for the colonial government, as it helped to ensure that the laws were applied consistently throughout the colony.

1777

An Act to enforce such parts of the Statute of Common Laws.

The following act was passed by the General Assembly of 1777 during the first session

14. An Act to enforce such parts of the statute of Common Laws as have been heretofore in force and use here, and the Acts of Assembly made and passed when this Territory was under the Government of the Late Proprietors, and the Crown of Great Britain; and for reviving the several Acts therein mentioned.

Note: In general, laws and acts that have not been repealed or overturned remain in effect until they are changed by subsequent legislation or invalidated by a court ruling. This means that if a law or act passed by the North Carolina General Assembly has not been specifically repealed or overturned, it is still in effect.

Tracing Land Records

1863 (1)

Hertford County 1863 Map.

Lists J.D. Myricks and W. Myricks and others as being owners of land where the 1729 Meherrin reservation is located.

1863 (2)

Map of the counties of Bertie and Hertford and part of the county of Northampton, North Carolina

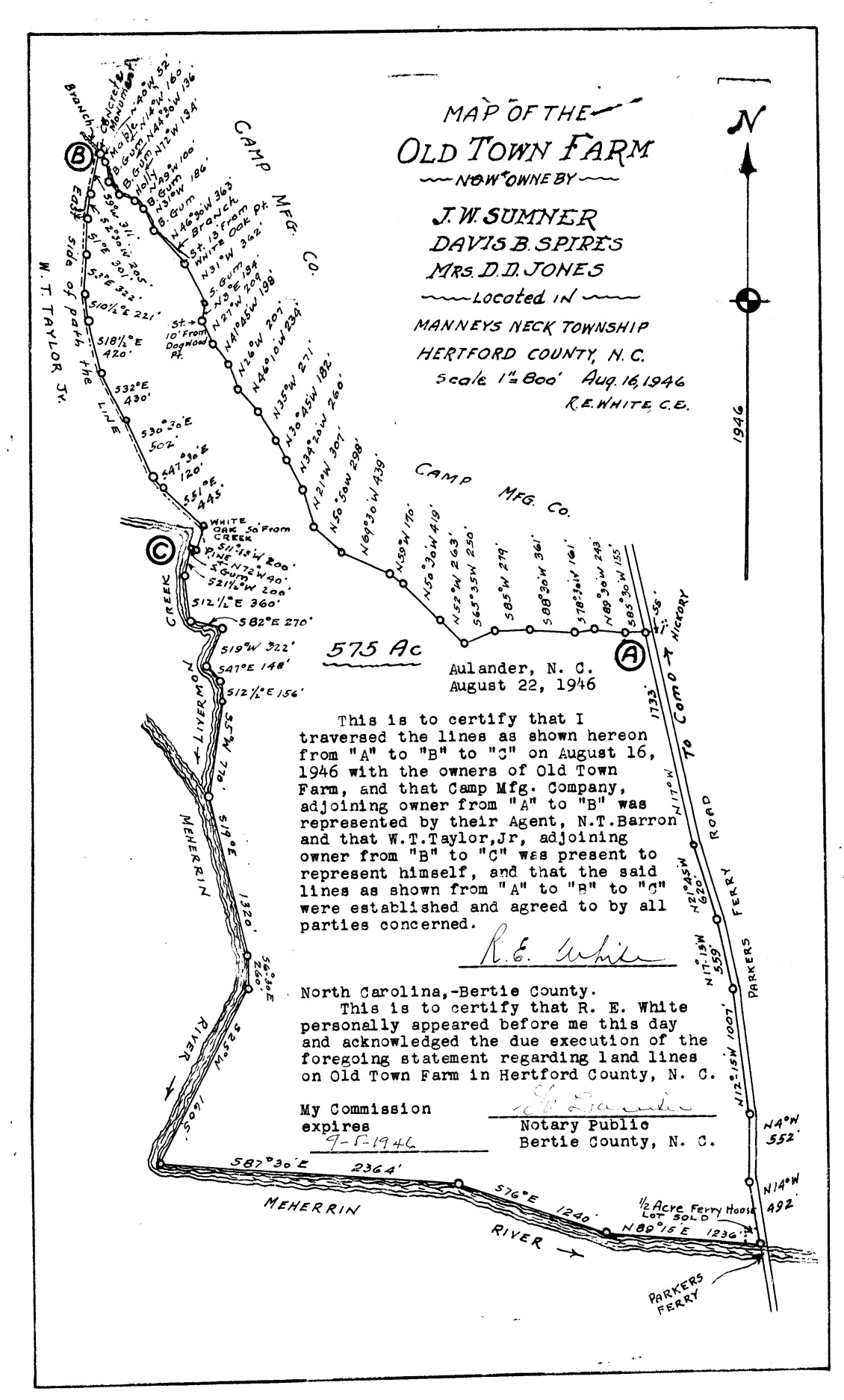

1946

Map of Old Town Farm, formerly known as Old Town Plantation, Old Town, Old Town Meherrin, and Meherrin Indian Town.

2023

The current location of Old Town Farm, formerly known as Old Town Plantation, Old Town, Old Town Meherrin, and Meherrin Indian Town.

1729 Reservation Lands today

As of today, the 1729 Meherrin Reservation lands are owned on paper by four main landholders, one of these being the State of North Carolina.

Notice: Our Tribe seeks to regain stewardship of our 1729 Reservation lands by collaborating amicably with landowners who currently hold them, as we work towards the repatriation of our ancestral lands.